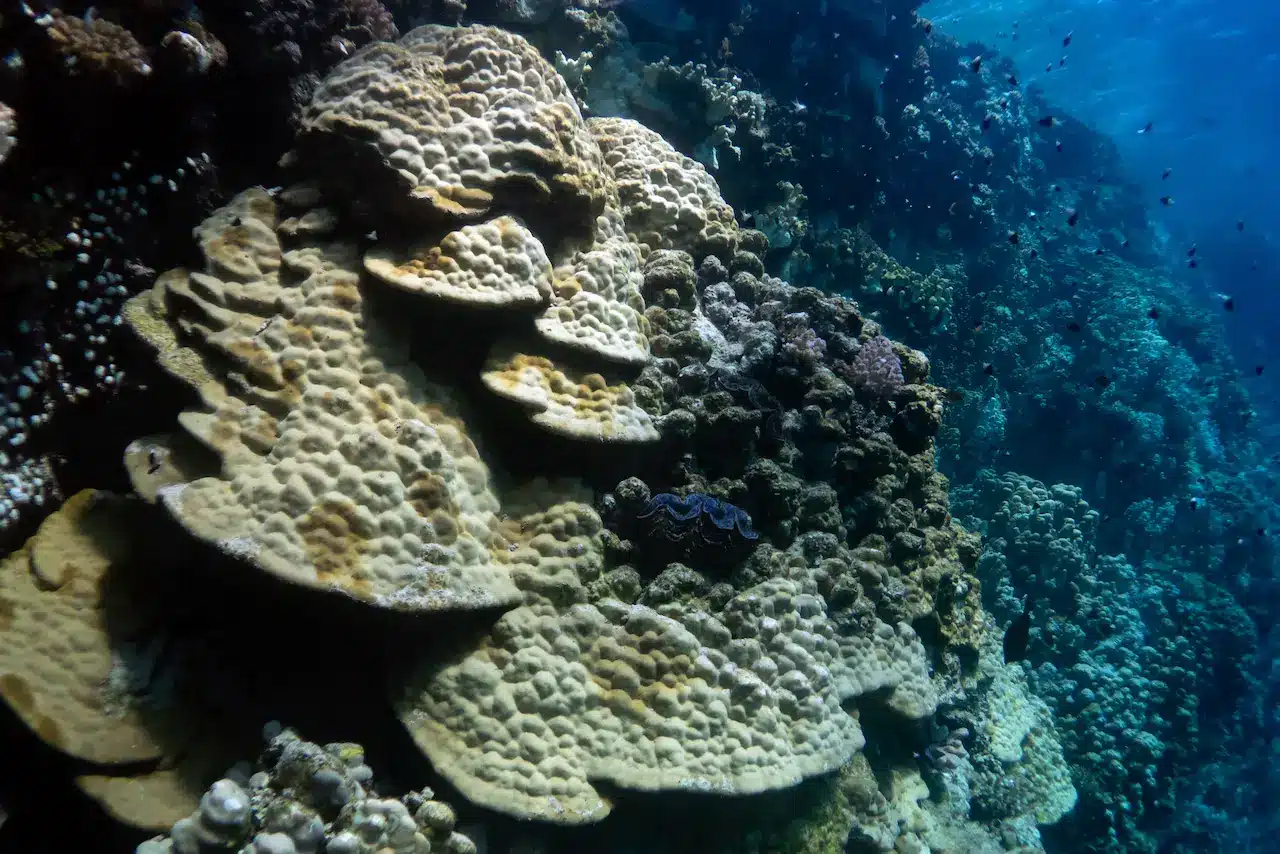

Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and valuable ecosystems on Earth. They support over 25% of all marine species and provide essential services like coastal protection, food security, and tourism revenue for hundreds of millions of people. However, coral reefs are under severe threat from ocean acidification caused by rising CO2 levels.

Over the last century, the ocean has absorbed around 30% of the excess CO2 emitted into the atmosphere from human activities. This has altered ocean chemistry and lowered the ph of seawater, making it more acidic. Ocean acidification makes it difficult for corals to build their calcium carbonate skeletons, which form the foundation of reefs.

Table of Contents

Toggle9 Ways to Save Coral Reefs from Ocean Acidification

If current trends continue, most of the world’s reefs may erode faster than they can rebuild within this century.

Urgent action is required to reduce CO2 emissions and implement measures to strengthen the resilience of coral reefs to ocean acidification. Here are some ways we can save coral reefs from the impacts of ocean acidification:

Reduce Carbon Dioxide Emissions

The single most important step is to reduce global carbon dioxide emissions by transitioning from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources. This will limit further ocean acidification and enable marine ecosystems to recover to healthier chemical conditions.

Governments, corporations, and individuals should actively seek ways to reduce their carbon footprint by improving energy efficiency, using public transportation, consuming less, and investing in renewable energy infrastructure.

Strong policies are needed to regulate emissions and incentivise clean technology development across sectors like power generation, transportation, manufacturing, agriculture, and construction. Investing in natural climate solutions like reforestation can also enhance carbon sequestration.

Protect and Restore Coral Reefs

Direct conservation and restoration efforts help protect corals from acidification and other threats like warming oceans, pollution, and overfishing. Marine-protected areas limit destructive human activities and enable ecosystems to function naturally.

Vulnerable reefs can be artificially strengthened by installing limestone structures that raise local ph levels and facilitate natural coral growth.

Coral gardening and reef regeneration programs that grow coral fragments in nurseries and transplant them to degraded reefs boost ecosystem recovery. Stabilising herbivore populations on reefs through fishing limits can control algae growth and support coral recovery.

Improve Water Quality

Reducing land-based pollution of nutrients, sediments, and other contaminants improves coastal water quality and alleviates stress on corals. Upgrading sewage treatment infrastructure, implementing sediment runoff controls in agriculture and mining, and using green infrastructure to capture stormwater runoff can reduce coastal pollution.

Banning certain harmful chemicals in sunscreens and cleaning products that find their way into reef environments can protect marine life. Strong environmental regulations and public education campaigns are essential to curtail coastal pollution.

Assist Evolution and Adaptation

While reducing environmental pressures is critical, corals will still need help adapting to the changes already set in motion. Assisted evolution techniques that selectively breed naturally resilient coral specimens can produce more tolerant populations for restoration efforts.

Identifying heat-resistant symbiotic algae to repopulate bleached corals may enhance thermal tolerance. Manipulating coral microbiomes through probiotics shows promise in promoting acidification resistance.

Gene editing is controversial but may become a last resort if conditions deteriorate faster than corals can adapt. Such human interventions are still experimental but might facilitate targeted adaptations.

Strengthen Multi-Level Governance

Saving coral reefs requires engaging communities, businesses, indigenous groups, civil society organisations, and governments at all levels. Their coordinated efforts and knowledge sharing through platforms like the International Coral Reef Initiative can drive local conservation and monitoring programs.

Improving public awareness and providing alternative livelihoods for communities dependent on corals can change behaviours. Businesses can develop sustainable tourism practices and help fund reef management.

Advancements in satellite monitoring and open data access can improve enforcement and accountability. Integrated policies across all stakeholders are key to aligning interests and building reef resilience.

Explore Unconventional Solutions

As climate change and ocean acidification accelerate, more extreme measures to manipulate seawater chemistry may eventually need consideration. Experimental techniques like seawater aeration that raises surface ph show localised benefits.

Supplementing reef environments with basic compounds like quicklime or seawater electrolysis to neutralise acids is being researched, but can alter natural biogeochemistry if not done prudently.

Coastal ecosystems can potentially be shielded from acidification through artificial barriers that limit exchange with open ocean water, but may have other ecological impacts. While unconventional, these approaches illustrate that multiple options exist if all else fails.

Foster Political Willpower

Ultimately, saving coral reefs from ocean acidification hinges on a stronger political commitment to address climate change. The fundamental solution is curbing emissions through energy transitions, which requires tremendous economic and social willpower in the face of vested fossil fuel interests.

Giving a greater political voice to young generations and frontline communities impacted by climate change can counter entities that obstruct progress. Legitimising environmental protection and climate action as part of a nation’s identity and ethics can generate public influence.

Electing governments that demonstrate authentic urgency and dedication to sustainability is essential. Activating society’s environmental consciousness to demand bold systemic change creates political incentives to take the strong climate action needed to save coral reefs.

Leverage Technology and Innovation

Emerging technologies and innovative solutions could help monitor, understand, and combat the impacts of ocean acidification on coral reefs. Developing more advanced sensors, analytic tools, and modelling capabilities would improve the detection of chemical changes in seawater and allow for better predictions of acidification effects.

Networks of automated ph sensors on reefs linked to satellite data could provide early warning systems to identify vulnerable areas. Artificial intelligence could analyse complex environmental datasets to derive targeted conservation strategies.

Genetic techniques like CRISPR may enable beneficial gene editing in corals and symbionts, but field applications require more research. Autonomous underwater vehicles and drones can survey remote reefs and collect vital data at scale.

Augmented reality could engage communities in virtual coral ecosystem experiences. Technologies should be applied cautiously and equitably while accelerating knowledge discovery.

Transition to Regenerative Ocean-Climate Economy

More fundamentally, transforming the global economic system away from carbon-intensive extraction and consumption is critical for the long-term flourishing of coral reefs. We need to redesign human activities of energy, food, materials, finance, transportation, and settlements in harmony with marine and terrestrial ecosystems.

Localised circular economies that reuse waste as input can close loops and lower emissions. Switching to diverse low-carbon protein sources like aquaculture, algaculture, or plant-based alternatives can reduce strain on wild fisheries. Ecotourism, payments for ecosystem services, and blue carbon financing can incentivise conservation.

Place-based approaches tailored to community needs and indigenous knowledge systems can develop context-specific solutions. Envisioning and actualising an economic system aligned with ecological boundaries will enable coral reefs and human societies to thrive mutually.

What is the best way to restore coral reefs?

Coral reefs around the world are under threat from a range of human activities, including overfishing, destructive fishing practices, pollution, global warming, and ocean acidification. Restoring damaged reefs is a major challenge facing marine conservationists. Some of the most promising restoration methods include:

Coral Gardening

Coral gardening involves growing corals in underwater nurseries and then transplanting them onto damaged reefs. Coral fragments are taken from healthy reefs and attached to substrates in nurseries.

Here, they are grown into larger colonies before being transplanted. The advantages of this technique are that it is relatively simple and low-tech. It also uses natural processes to grow corals.

Artificial Reefs

Artificial reef structures made from materials like concrete, steel, or fibreglass can be lowered onto damaged reefs to provide a stable platform for new coral growth. These structures mimic the complex 3d structure of natural reefs.

They are also designed to be stable in storms and resistant to threats like coral predators. The benefits are that artificial reefs can be tailored to specific restoration sites and can restore 3d structures rapidly. However, care needs to be taken with positioning and design to ensure long-term integrity.

Electromineral Accretion

Electromineral accretion (EMA) uses a small electrical current to accrete minerals dissolved in seawater onto steel structures. This rapidly forms a limestone coating that provides an ideal substrate for corals to settle and grow on.

EMA technology has been used successfully to create large artificial reef structures in just a few months. It is a promising technique, but requires further research and development to scale up.

Assisted Evolution

Assisted evolution techniques aim to adapt corals to be more resilient against threats like warming seas, acidification, and disease. This can involve selecting heat-tolerant micro-organisms (algae) to pair with coral, propagation of resilient coral species, or gene editing.

These interventions aim to accelerate natural evolutionary processes. However, these emerging technologies require continued research to ensure they are effective, ethical, and safe.

How can we prevent ocean acidification and coral bleaching?

Ocean acidification and coral bleaching are major threats facing coral reefs globally. But there are actions we can take to prevent further damage:

Reduce Carbon Dioxide Emissions

The main driver of ocean acidification is rising carbon dioxide emissions, mainly from burning fossil fuels. To limit acidification, we urgently need to transition to renewable energy sources and achieve net-zero emissions.

Individuals can contribute by minimising their carbon footprints. Governments and businesses also need to implement policies and plans to drastically reduce emissions.

Protect Shallow Reefs

Shallow water coral reefs are most at risk from bleaching during marine heatwaves. Protecting these vulnerable reefs by limiting direct human impacts can improve their resilience.

Strategies include designating protected areas, reducing runoff and pollution from the land, preventing ship anchoring damage, and sustainably managing tourism.

Reduce Local Stresses

By reducing other stresses on reefs, such as overfishing and destructive fishing, pollution, and runoff, we can strengthen the overall health of coral reefs and their capacity to survive acidification and bleaching. Improvements in watershed management and wastewater treatment are important interventions.

Assist Reef Migration

As oceans warm and acidify, some corals may migrate to more optimal habitats. Installing artificial reef structures in areas projected to have future optimal conditions for coral growth could assist their migration and settlement. Restoring connective habitats like mangroves and seagrasses can also facilitate natural reef migration.

Increase Herbivores

Herbivorous fish and urchins help prevent seaweed overgrowth on stressed reefs. By sustainably managing fish stocks and limiting the catch of key herbivores, reefs are likely to fare better during bleaching recovery. Artificial stocking of larvae or juveniles can also boost grazing pressure on struggling reefs.

Strategic Shading

Installing structures on shallow reefs to provide shading has been trialled as a way to lower temperatures during marine heatwaves and reduce bleaching.

Studies show daily shading of as little as 30% of the seabed during summer middays can prevent bleaching. But shading needs to be strategically deployed to avoid unintended consequences.

What is the solution to the damage to coral reefs?

The multifaceted nature of threats facing coral reefs globally means that an integrated solution is required:

Global Action on Climate Change

As atmospheric CO2 is the key driver of warming seas, ocean acidification, and increased frequency of coral bleaching events, urgent global action to mitigate climate change is needed to enable coral reefs worldwide to survive and recover their former glory.

Local Protection and Management

While climate change mitigation is essential, local action to protect reefs from direct damage provides them with the best chance to withstand and recover from global impacts. This requires management approaches tailored to individual reefs and community stewardship.

Active Restoration

To catalyse the recovery of degraded reefs, active restoration efforts are needed, such as coral gardening, installing artificial reefs, and using technologies like assisted evolution. Natural recovery may no longer be enough for many overexploited reefs.

Integrated Monitoring

Regular and sustained monitoring of reef conditions provides managers with timely interventions and solutions. It also enables the success of programs to be tracked reliably. Monitoring reef health, water quality, and fishing impacts is key.

Sustainable Tourism Practices

Many reefs face heavy pressures from tourism activities. Developing sustainable tourism, such as ensuring that carrying capacities are based on science, education of operators, and tourism user fees that support management, is part of the solution.

Investing in Innovation

More investment and research are required to develop and refine solutions such as helped evolution techniques, bioremediation, strategic shading, and EMA accretion to enable viable large-scale restoration in the future. Innovation and flexibility will be key.

Community Engagement

For any reef management initiatives or restoration programs to work, they must engage the community. Building stewardship through education programs and interactive tourism are examples of local engagement that is vital to achieving local buy-in and compliance.

Can corals survive ocean acidification?

Ocean acidification is a serious threat facing coral reefs worldwide. But research suggests some corals will be able to adapt and survive acidifying oceans:

Variations Between Species and Locations

Studies reveal considerable variation between coral species and locations in the impacts of acidification. Some corals and reef ecosystems appear more naturally resilient to lower ph than others. Understanding this variability can guide conservation efforts.

Adaptation Potential

Many corals may be able to adapt to gradually acidifying water over the coming decades by changing their skeletal growth, forming more robust structures, or altering their symbiotic partnerships. However, the rate of change is a key factor in adaptation potential.

Refuges from Acidification

Parts of coral reefs with naturally lower and more variable ph, such as intertidal reef flats and back reef lagoons, can act as refuges. Expanding these refuges through the creation of lagoons as buffers could aid the survival of vulnerable species.

Assisted Evolution

Emerging assisted evolution technologies that allow heat-tolerant algal symbionts to be paired with coral larvae offer the promise of breeding resilience to future warming and acidification. These interventions may provide a lifeline for struggling reefs.

Protection from Local Stresses

Minimising other localised stressors on reefs, such as pollution, sedimentation, and destructive fishing, gives corals their best chance of surviving the global threat of acidification. Boosting overall reef health builds resilience.

Active Restoration

Proactive restoration of damaged reefs using techniques like coral gardening assists ecosystem recovery and provides insurance for populations to maintain reefs through the coming challenges. Restored reefs are likely to better withstand acidification.

However, their long-term survival under relentless acidification ultimately depends on the urgent reduction of carbon emissions globally. This is critical to enable these surviving coral refuges and assisted corals to re-establish thriving reefs in the future.

Conclusion

Stemming ocean acidification and boosting coral resilience requires a multi-pronged strategy of reducing carbon emissions, improving coastal environments, assisting coral adaptation, strengthening governance, exploring unconventional interventions, and generating political willpower for more ambitious climate action.

A mix of local reef management and global policy to curtail CO2 input into the atmosphere is needed to create conditions suitable for coral recovery and survival in our rapidly changing oceans.

With committed efforts across all sectors of society, we can transition toward a carbon-neutral economy and hopefully preserve these invaluable rainforests of the sea for future generations. But action is urgently needed now before it is too late.